This article relates to work performed within lectures and lab sessions of an AI module as part of the Games Technology undergraduate course at Coventry University (2016/2017).

In this week, we covered movement and path-finding for video game AI and what is necessary for implementation. For example, take the pseudo-code algorithm of creating an aggressive entity, such as a swordsman:

if (enemy is in range)

if (enemy.hp > you.hp)

block attack;

else

enter combat;

This kind of thinking for an AI is like looking at a decision tree, with yes and no as it’s answers for furthering down the hierarchy. The practice of doing this through AI is called ‘action selection’. While the above code can work, it would be much more detailed with more levels to it’s hierarchy. But it can also apply itself to movement. Is the AI in range to hurt the player? No? Then decide to move closer to them.

If the AI can/does move in the environment, how would it go about that? Does it move as a single entity or as part of a group? Does that group move identically, such as in formation, or can they move similarly, such as near to each other? RTS games would make units that are portrayed as small groups move identically (unless there is a collision) whereas an FPS would make the group of enemies in a room move individually of each other but still aware of their allies. This behaviour is expressed as a group called a “boid”. Think of a boid as a flock of birds and how they fly through the air when migrating. A boid will likely have a certain range at which it will be effective; individual behaviour won’t be affected by entities halfway across a large open world map, for example.

Boids can create the illusion that all covered entities operate as one unit and are clever due to their general constraints:

- Uses three types of steering behaviour, to avoid crowding (Separation), steer towards average heading/angle (alignment) and move towards average position (cohesion).

- Can sense similar entities within a certain predetermined area to control behaviour

- Each entity in a boid has a distance and angle variable, determining how far and wide any entity can “see” other entities. Then, using the three steering behaviours, applies a weight and determines the strength of the behaviour on that entity using each component of the steering variables.

Of course, this can be expanded upon based on the game’s requirements, such as applying a morale value; are the entities scared if a lot of the previously existing entities in the boid have disappeared from view in a short time? Or is it possible for each boid to avoid colliding with objects as a group or individually between each entity? Can a patrol be set up, such as a repeatable path? has one entity engaged the player and do the other entities follow this behaviour?

Path-Finding Techniques

So the AI behaviour is capable of changing based on it’s environmental constraints and if individual behaviour changes at any time? How would that entity move to appropriate place int he world? How would it detect that it can move there. The AI needs to be told a method of performing this. Using a program called “Path Finding Demo” by Bryan Stout, it is possible to see a visual representation of path finding occuring on a grid based system. The two that have been researched this week are Dijkstra’s algorithm and the A* system. Any path finding algorithm needs to be able to find the shortest path in the most efficient time possible. Therefore, both need to be analysed on their structure and their strengths and weaknesses.

Dijkstra

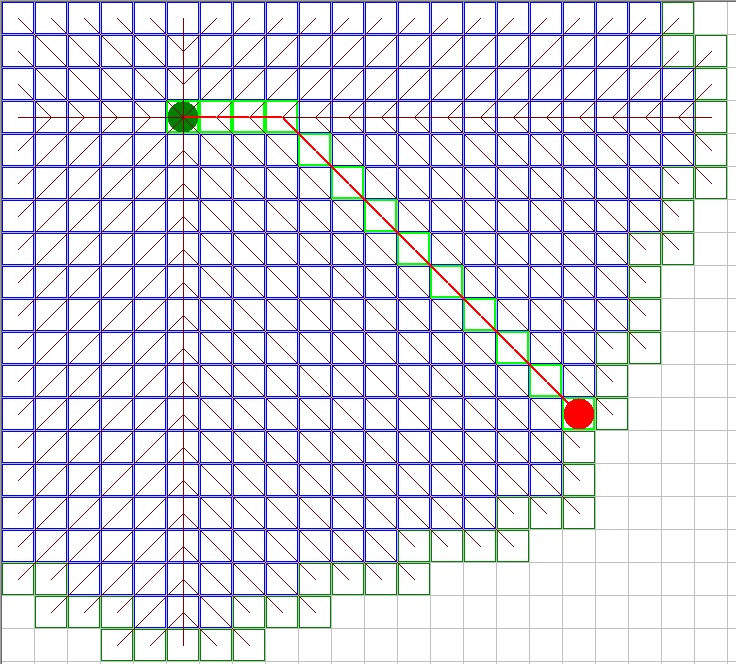

This algorithm uses a starting point and will visit all surrounding possible vertices. After it has done this once, it will iterate, finding all possible vertices beyond those found in the previous iteration. The algorithm does not the end goal’s position and so, doesn’t actively search for the closest vertex it can take (no weighting applied). This means that over large distances, it will take a very long time to determine any direction to take as it will assess every possibility. Examples of this working are displayed below, one which is simple for the algorithm to work with and one which requires more time to calculate based on non-weighted decisions:

A*

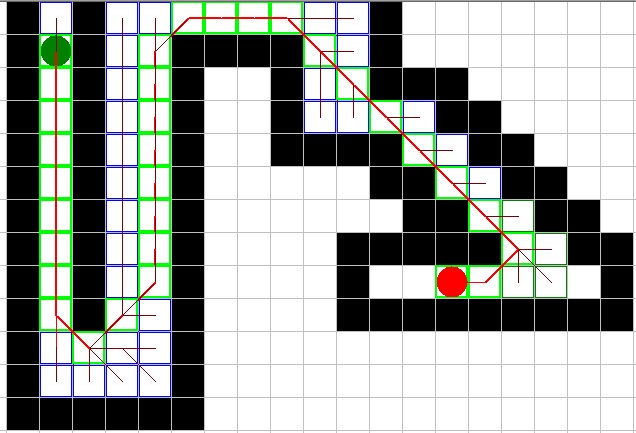

Using similar conditions as Djikstra, the A* pathing works better than Dijkstra in an open space due to it’s weighting accountability but mostly the same within the very constrained environment of walls, as shown below:

So both have strengths and weaknesses, Djikstra does not work efficiently over a large open area but A* does however, A* will likely collide with many more objects in trying to use a heuristic to find the goal (the weighting) in enclosed spaces. Therefore, the best method for implementation would be determined by how many obstacles are likely to be in the way of any entity at any one time. In an arena, it is highly possible that there are many walls and as such, could affect AI if A* is used. This will need to be tested properly in implementation however, it seems as though an alternative method might be necessary.