Recently, a new Yu-Gi-Oh mobile game was released by Konami to coincide with the worldwide release of the anime’s new big screen outing. This is the first time the series has been brought to smartphone platforms, reaching perhaps its biggest digital audience since inception. It is a fast, stylish and enjoyable mobile game, perhaps one of the best currently offered. In making the series reach the mobile audience, some corners have been cut, likely to accommodate for the variety of phones/tablets players will use, and the game has been made much simpler than full retail versions that have been previously released.

The game’s AI however is the biggest change.

In previous installments, the AI could be ruthless and unforgiving towards the player, easing them in at first but dishing out near perfect strategies as they continued. They also boasted having the entire catalogue of the real life card game at the time of development, giving players the chance to use any and all strategies. Duel Links doesn’t have either of these granted to it for a good reason: many people will be playing Yu-Gi-Oh for the first time.

Traditionally, Yu-Gi-Oh is set up as the following:

-

Two sides, one for each player

Two main sets of Zones; with five spaces for Monster and Spell & Trap Zones

Zones for the player deck, an extra deck of special monsters and the graveyard (discard pile)

A special space for cards that affect the entire field

A value of 8000 Life Points

A Deck with a minimum size of 40 cards, 60 max

In Duel Links however, this has been changed to work with smaller conditions

Instead of the five spaces for non-special cards, there are only three. Player Life Points start at 4000 and there are less than 40 cards in the deck on the first turn. These smaller constraints actually work in favour of the game. Phone users are less likely to play for sustained periods of time, such as over a lunch break at work, or after school for younger users. By scaling down the constraints of the original iteration of the game, it makes sense to also constrain the opponents to lower standards, to make all of these aspects work for the first time player and it does. Except it goes too far.

In this screenshot, the monster card played by the AI was placed on the field after my turn had ended. So the AI knowingly placed a card with a lower ATK stat (the top number) on the field whilst its opponent had something much stronger. Lower difficulty AI do this constantly, across every character. The problem still exists at the highest level of AI opponent, albeit less frequently, though this can also be attributed to higher level opponents having better constructed decks provided by the game.

While it appears that the AI is not very intelligent at dealing with opponents properly, this isn’t fundamentally the case. In making a card game, of similarly scaled ilk, such as Hearthstone and Magic, there is an incredibly large amount of context specific situations that AI will have to deal with. What cards are in their hand? Can it play them given the current field conditions? If they can, how do they play them? In what order should this be done for maximum effect? If there are multiple possibilities of reaching the same conclusion, what is best in the short term and what is best in the long term?

As one of the flag ship real-life card games, Yu-Gi-Oh has an extensive library, boasting nearly 8000 unique cards that are produced worldwide (Japan has a range of exclusive cards). Having an AI system deal with cards that have different & specific effects on a majority of cards (monsters are easier to apply than spells and traps, which are even more specific in execution) whilst also tailoring their use to appropriate situations is a complex task. For this reason, Konami released the game not by releasing every single card but by including a small selection (~250) of choice cards, primarily original generation cards spanning its first few years. There are new cards peppered into the mix however, simplicity wins over complexity.

MiniMax Theory and Decision Tree Logic

Yu-Gi-Oh is played in sequential turns, and allows for any number of cards to be played during each of these turns. This leads to any combination of strategies being played at any time. For an AI, this becomes less clear than a simple yes or no in deciding which card(s) to play for a given situation. It needs to analyse the current game state and decide what should happen next. However, as expressed above, the AI will perform moves that are not optimal i.e. playing a lower ATK stat monster than its opponent’s current monster(s). While there are issues outside of just the AI, such as the deck’s cards not being superior, it is clear there are issues with something in how the AI decides to play. So let’s look at how the AI appears to work on a technical level.

Each AI character is given a pre-determined deck of cards to use every time you play against them. These decks change based on their difficulty level as you progress higher through the ‘stages’ (profile level) or as you choose the level to compete against characters from the anime at. While there are many different characters, it would seem, through experience, that each character is defined by the same AI logic, as opposed to one that might mimic the character they are portraying (more aggressive or defensive types, for example). This cuts corners on production time however, it also means every character has the same flaws (see above) when you play against them. A positive to this however, is that they are all able to effectively work with each of the cards presented to them. Almost every card has unique effects and conditions for playing them, with equip spell cards needing to have a free spell or trap zone space, a monster card out on the field and, for some cards, that monster needs a specific type (e.g. dragon or warrior) as one such set of conditions. Therefore, there must be an efficient way to get through whether or not the AI decides it can play the card it wants to use whilst also making sure it doesn’t take too long to make this decision. So what method could Duel Links implement?

Decision Trees

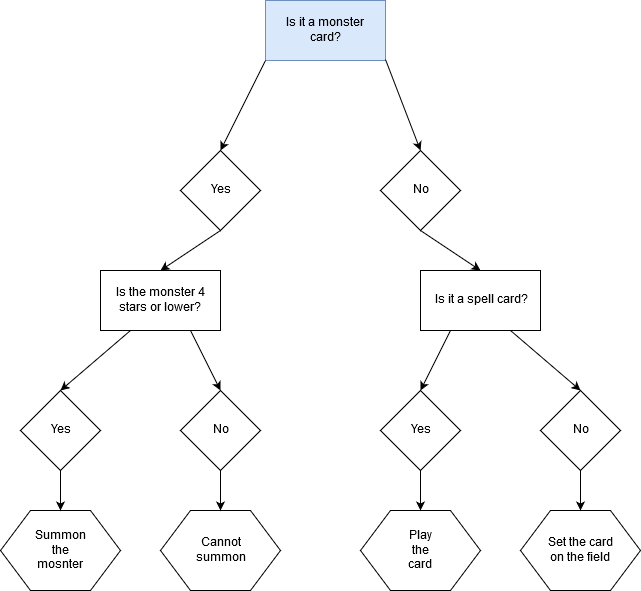

To circumvent making code for each card that performs condition checking, it is much simpler to create an overarching set of options that every card can perform. Is the card a monster? If not, it has to be a spell or trap. Then you can ask if it’s a spell? If it is, you can ask which type it is. By being specific enough to receive a type, you can be vague enough to require specifics without actually calling every line of code required. It also makes deciding if a card cannot be used much quicker, as there are less checks to perform, in most circumstances.

Below is a sample tree that the AI could follow for a card. It is basic but it gets the point across on the typical behaviour on display.

By conditioning like this, it is possible to move through a set of binary choices very quickly to reach the intended goal (the card and it’s effects) without being specific to that one card but specific enough to understand that it is a certain card that works dependent on its categorisation within that type and whether or not it is playable.

MiniMax Theory

The Encyclopaedia of Mathematics staes on the MiniMax Theory the following equation:

“An optimality principle for a two-person zero-sum game, expressing the tendency of each player to obtain the largest sure pay-off

Yu-Gi-Oh can be expressed somewhat like this, with the potential to place a card and gain a one up on tactical advantage, a zero if a card is used to remove an opponent’s card that leaves at the same time or a one down if they use a card to remove one of yours whilst theirs stays on the field. As opposed to Infinite Game Theory, any game is confine the set of strategies presented by the current field and as such, is easily limited in scope every time a calculation should be made to judge performance, making MiniMax the more relevant theory here. Therefore, combining both this theory and decision tree logic the AI should, in principal, create the best situation in which to present itself to the player. This however, is sadly not the case.

Final Thoughts

Moving to the mobile market was certainly a good move in bringing the Yu-Gi-Oh franchise to a larger market, beyond the old games released (mostly) on portable consoles. However, in order to accommodate with behaviours of the mobile market, the game couldn’t be made too difficult, hence the change. However, it went too far, making AI opponents become less of a challenge at lower levels that they require little strategy but making the difficulty ramp up, in some cases, greatly at the higher end. This causes a giant rift in terms of difficulty curve and can be accounted for by all aspects of the game though the way the AI has been weighted or setup definitely account as a large factor of the problem.

Header Image can be found here